Digital Twins were first used in the Apollo program in the 1960s, consisting of simulators, advanced for that time, as well as physical replicas of the spacecraft modules. These first Digital Twins were essential in avoiding a fatal disaster during the Apollo 13 mission. Although Digital Twin technology has come a long way since then, it is still one of the most promising development areas with the potential for creating value in the aviation industry. Today, Digital Twins seek to maintain the digital replica of an asset or system throughout its lifecycle requiring continuous data feeds. That’s where the Digital Thread comes in.

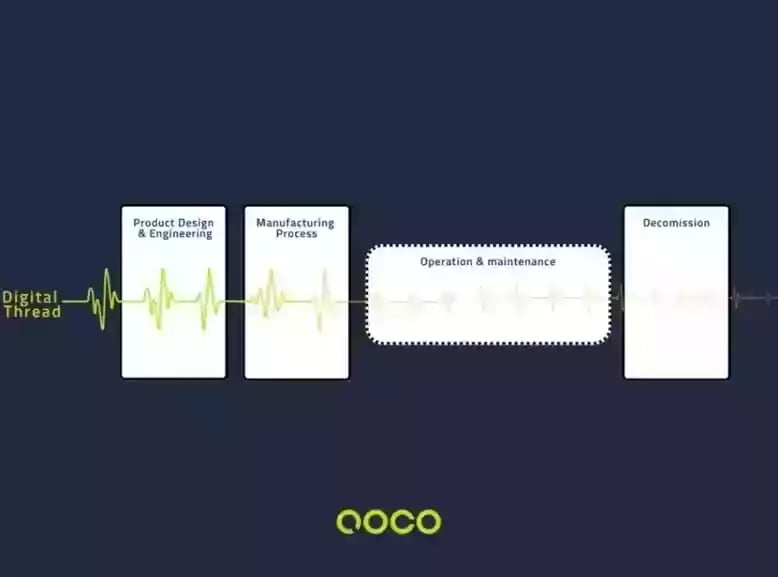

A Digital Thread is made up of all the records and data generated and stored throughout the lifecycle of an asset, from design to operational use and retirement. Imagine a thread running through time, buzzing and glowing with all the information generated about the asset. This information includes automated and human-made digital records, as well as sensor data generated by the asset itself. The Digital Thread lays the foundation for the Digital Twin, meaning that the more data that is continuously gathered about the asset, the more reliable and detailed the Digital Twin will be. Modern engines and aircraft generate ever larger volumes of sensor data, increasing the value potential of data-driven solutions. The digital records, in turn, are essential for understanding the context of the sensor data as, without them, the raw sensor data is less valuable, or even worthless. More on these two categories later in the article.

In his article “How I See IT: Digital threads and twins in MRO” Allan Bachan presents ICF estimates for Digital Thread maturity throughout the aviation asset lifecycle. These estimates show that the Digital Thread maturity is high at the beginning of the lifecycle, during the engineering and manufacturing of the asset, but drops significantly when the asset is in its operational phase. You can imagine the glow of the Digital Thread dimming once the asset enters service, causing the Digital Twin to become less reliable and detailed.

Reference: Aircraft IT MRO — March/April2020, Allan Bachan

For the rest of this article, I will focus on the lifecycle Digital Thread maturity from the original equipment manufacturer (OEM) perspective. When the asset is in operational use there are several stakeholders with a vested interest in the digital twin. The main stakeholders are the operator, OEM, MROs and lessor. Since these stakeholders do not have shared access to all generated data, the challenge in maintaining the Digital Twin becomes the accessibility of the generated data. This accessibility for the OEM drops drastically as the asset enters into service.

Typically, the OEM lacks access to the majority of data generated during operational use of the asset, yet has much to gain from maintaining a high-quality Digital Twin. Analytics-based insights from Digital Twins feed into the OEM’s product development process, but also allow them to offer value-added services such as health monitoring and predictive maintenance, enabling extended, predictable and more reliable operation for the operator. The digital twin also enables the OEM to offer performance-based contracting, such as Rolls-Royce’s ‘Power by the Hour’ lease model, in which the customer is billed based on actual utilization of the asset.

During the operational phase of an asset, there are two main categories of generated data; sensor data generated by the asset, and digital records generated by information systems and people. These categories of data are fundamentally different in the following aspects:

Sensor data recorded by the asset is designed to be shared and utilized for analytics and digital twins, and is mostly standardized across assets used by different operators. While sharing this data is technically straightforward, many operators will opt out unless the OEM is able to present a solid value proposition in exchange for sharing the sensor data.

The records data, which is mostly stored in the asset operator’s Maintenance and Engineering (M&E) system, is more challenging. This data contains asset maintenance and utilization records, asset configuration and defects, which are all essential for maintaining a digital twin. Integration capabilities of M&E systems vary and there is little standardization for the data stored. Even operators using the same M&E system will have variability in stored data due to differing processes and practices. Consequently, it is a challenge for the OEM to collect the digital records of assets in operation with their customers.

However, while the challenge is great, so are the potential benefits. An accurate Digital Twin based on up-to-date data from both data sources allows for substantially more value to be extracted from the twin than a model based on only one of the data sources. OEMs utilize Digital Twins for advanced asset performance monitoring. Digital Twins also provide valuable insights into the product development process. However, the main benefit is the capability to provide value-adding services to operators, such as fleet health monitoring and predictive maintenance, ultimately providing the OEM with a competitive edge.

Then the question on the mind of an OEMs is: How can continuous, standardized and reliable data exchange with operators be implemented for the digital records? This question deserves its own article and will be covered in my next article.

Streamline your data exchange processes effortlessly with Aviadex.io. Our platform allows collaborators to integrate once and selectively share data with ease, eliminating the need for manual data entry and reducing complexity. Experience the future of data exchange today.

Henrik Ollus

Henrik Ollus

If you are interested in knowing how you can improve your efficiency in maintenance operations, book a 30-minutes discovery call with us.

If you are interested in knowing how you can improve your efficiency in maintenance operations, book a 30-minutes discovery call with us.